Table of Contents

What is business academia?

Business academia is split into numerous fields and subfields within which you must identify your particular interests. In general, business school research draws from a set of disciplines such as economics, sociology, psychology, and to a slightly lesser extent other fields such as history, statistics, and political science. Over time, business school researchers have developed their own fields such as organizational behavior, accounting, finance, and strategy. The best way to gain an understanding of these fields is to look at the types of academic articles that these researchers are publishing. It is important to have a general sense of the field of your interest and the types of questions that it does (and does not) cover.

What do professors do?

But what is it exactly that professors ‘research’? How do professors allocate their time? And what are the various duties expected of a professor? This section attempts to answer these questions.

The first fact to consider is that research in the Social Sciences is somewhat different from research in the traditional sciences of say Physics or Chemistry. The job of Social Scientists is to comment upon the way things work in the world around us. Researchers in B-schools are particularly interested in questions that concern firms of various types. This could include thinking about how consumers react to user-generated content on the internet (Marketing or Information Systems), how retailers organize their supply-chains (Operations), how large firms might compete with rivals in a specific market (Strategy), how boards manage shareholder returns (Finance) or how organizations adopt practices that would make them more responsive to change (Organization Behavior).

This is only an indicative list and there are two points to be considered. First, the classifications I list in parentheses are synthetic and it is not uncommon to find Strategy researchers working on issues in Corporate Finance or Information Systems researchers working on Supply Chains. While it is true that each of the above departments has its own ‘core’, a lot of exciting research happens at the boundaries of two or more departments. Second, the questions I list are often too broad for one particular research project. While it is generally true that a particular Corporate Finance researcher might think about issues concerning shareholders, a particular paper will often make a very nuanced argument that builds upon past research. In fact, it is important to understand that the nature of research is very much in Newton’s “stand upon the shoulders of giants” spirit than is commonly acknowledged.

Given that we now understand the kinds of broad questions that business researchers might think about, the second fact to consider is the disciplinary and methodological foundations upon which such research is based. ‘Business’ (or ‘Marketing’ or ‘Finance’) relies heavily upon the basic disciplines to build its theory. The three most common disciplinary lenses used are Economics, Sociology and Psychology. However, one of the attractive features of research in business is the ability to draw upon a number of these disciplines to make theoretical and empirical claims; hence the term interdisciplinary is often used in conjunction with business research. Each of the basic disciplines has a theoretical core which is based upon certain assumptions. Economists for example, often assume perfect or near-perfect rationality and profit-maximization in their theoretical models. Business research will then apply disciplinary theories in a business context. Different researchers within Business will draw upon the basic disciplines in a variety of ways. For example, those studying Consumer Behavior (in Marketing) or Behavioral Finance might considerably draw upon Psychology while those in Strategy might use a combination of Economics and Sociology to meet their goals.

Further, researchers often sort themselves into theoreticians or empiricists. A theoretical person in marketing might build game-theoretic models to explain a certain pattern of market interaction, while an empiricist will often gather and analyze real-world data from a variety of sources to build econometric models to test her theories. Different methods and disciplines require a widely varying level of mathematical sophistication (the standards for which vary considerably in different circles) and where one might sort oneself is largely a matter of taste. Increasingly, business research is empirical and a number of researchers are using econometric techniques to generate insights from large data-sets. Constructing these data-sets and running statistical tests on them can be quite challenging (and tedious!). While there are many types of academics and an equal number of tools that they employ, accomplished researchers are unified by their ability to identify important problems and write about them in a theoretically rigorous yet interesting way.

Research methods, their classification and the philosophies that motivate them is a vast topic that is beyond the scope of this note, but a certain idea of their existence and their relevance to the field under consideration is important.

A business school PhD -- what is it and should you do it?

Why apply to a business school PhD program?

The most common reason to pursue a PhD in a business school is to become a business school professor. In most business schools nearly all tenured faculty members have doctoral degrees from either a business school field (e.g., management, finance, marketing, etc.) or a related discipline (e.g., economics, sociology, psychology, etc.).

PhD programs in business schools can take many forms. Business research can take a highly quantitative approach – as in the case of business economics, accounting, or finance – or use qualitative methods such as ethnography. Research methods could include experiments, interviews, or the analysis of large datasets. What unites these disparate approaches is A) the connection between the research and the practice of doing business and B) that most PhD graduates intend to become faculty members at business schools.

If you have just started considering a PhD in business, you should seek to gather as much information as you can about what this career path entails and the degree to which it suits your interests and goals. This guide is a good start, but you may also consider attending a DocNet fair where you can meet with and learn from business school admissions staff. If you are a member of an underrepresented minority, you should also look into the PHD Project, which is an excellent resource for learning about the profession and connecting to mentors. Members of underrepresented minorities may also be interested in the IDDEAS (Introduction to Diversity in Doctoral Education and Scholarship) program, which is hosted annually at business schools such as MIT Sloan, Wharton, Kellogg, Booth, and Stanford GSB. It is a two-day immersion program that introduces undergraduate students to business research at the doctoral level, academic careers, and provides insights on the application process.

How does being a business school professor compare to other careers?

To begin, it’s important to understand what areas of a career matter to you – whether they be income, autonomy, impact, etc. It’s clear that there are many benefits to a life as a business school professor – but also serious drawbacks.

For one, numerous researchers have documented the poor mental health of graduate students. One 2018 study conducted by researchers at Harvard, for example, showed that economic PhD students are three times more likely to show depressive symptoms than the average population (Barreira, Basilico, & Bolotnyy, 2018). It is worth noting that economics PhD programs may be harder on students’ mental health than most business programs, but we recommend looking into the large body of research on mental health issues in graduate students across a variety of programs. A PhD can be pressure-filled and the relatively small stipend can become a serious stressor for many students. Additionally, as many students argue, it’s hard to feel a sense of “progress” day-to-day. When the output is generating novel, innovative research, it is often unclear whether or not you’ve made progress towards that goal each day.

In addition, many PhD students face a significant opportunity cost by attending a PhD program – particularly a business school program. It is important to recognize that individuals who successfully become business school professors are generally highly educated and talented. That is to say, they have a skill set that would allow them to work successfully in other careers. In fact, PhD students who do not enter into academia often enter into other fields such as finance, consulting, and tech. Nonetheless, there are also numerous benefits to a PhD and business school academic career, including intellectual fun, autonomy, and a uniquely flexible lifestyle post-tenure.

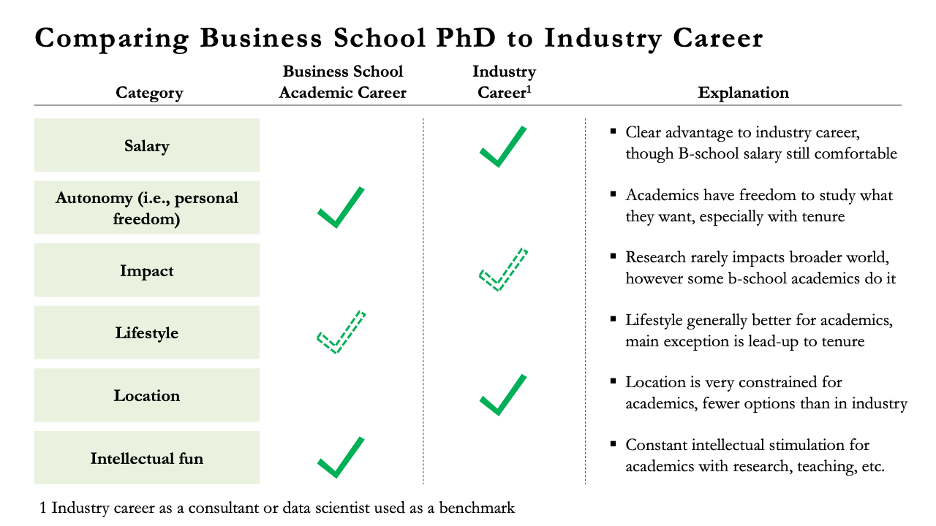

Linked below is a general comparison of a business school professor’s career to one in industry. In general, professors win out on autonomy, lifestyle, and intellectual fun, but earn less and have fewer choices in location.

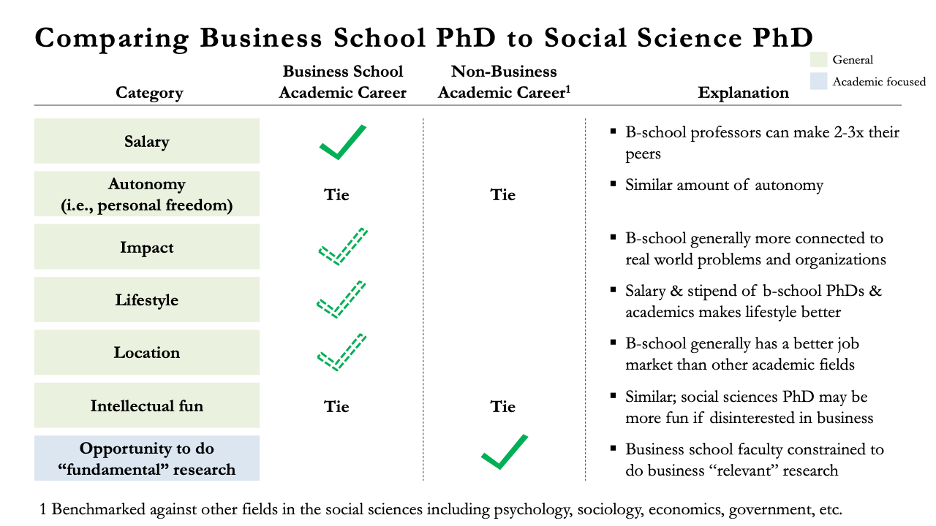

Individuals considering a PhD in business may also be interested in an academic career in a related field, such as economics, sociology, or psychology. For this group, it is useful to compare the career of business school academics to other academics.

When making a comparison based on these factors, business school academic careers win out over other academics in social science fields in most scenarios. One important caveat to this hinges on your ability to do “fundamental” or “basic” research. Because business schools exist to support managers and leaders, there is an expectation that your research be somewhat “applied” and connected to the practice of management. More fundamental topics (such as understanding personality changes across the lifespan which falls into the realm of basic psychology, or studying the structural elements of a machine learning algorithm which falls into the realm of computer science) can often fall outside the scope of business school research. If you are interested in studying an important topic that does not fit within the umbrella of business, then you may be more fulfilled pursuing a PhD in another discipline.

The main reason why business school academics are paid more (generally starting around $180 - $200k and then going up to $300-$400k) is because of their exit opportunities. If they left their career as an academic, they could command significantly higher salaries in industry, which is not necessarily true for academics in other fields. Another reason why business school salaries are generally higher is because business schools bring in more revenue to spend on attracting high quality faculty members and supporting their research. It is important to note that salaries likely vary by discipline (finance and strategy professors often command the highest salaries) and by school (more prestigious schools may be able to offer higher salaries).

What impact do business school professors have on the world?

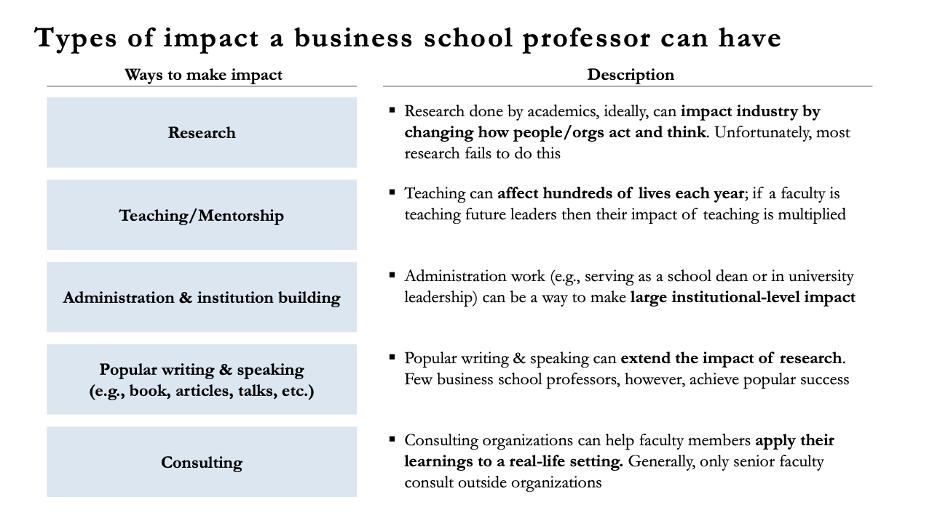

In the comparison table above, we give industry careers a slight edge on the “impact” dimension. This begs the question: what type of impact do faculty members have on the world?

The reason industry careers may be judged as more impactful is that most business academics are solo contributors. This means that unless their research is picked up broadly – which is relatively rare – they will not be able to leverage teams and organizations to extend their impact as their industry peers do. In general, the distribution of the impact of academia has a long right tail, with research from a few superstars having significant influence, and most academics not achieving widespread exposure. Academics can combat this limitation by teaming up with other researchers or by developing academic organizations to expand the impact of their work (for example, founding a research lab or an institute in their particular area of interest).

What is the lifestyle of a business school professor?

A significant benefit of any faculty position is the autonomy. Professor and PhD students have the freedom to choose when and how to work. Generally, academia is a path that enables immense flexibility and self-direction.

Becoming a professor is a great way to engage in a lifetime of curiosity and learning. Professors often spend their days trying to learn about and answer questions that they find interesting. Unlike an industry career with its constant pressures towards commercial ends, professors are generally shielded from the day-to-day press of paperwork and profits.

How difficult is it to become a successful professor?

Unfortunately, even if you do complete a PhD, there is no guarantee that you will secure a job as a faculty member. The job market for assistant professor positions is quite competitive and most PhD graduates accept job offers at schools a rung or two lower in prestige than their degree-granting institution (Clauset, Arbesman, & Larremore, 2015). This 2015 study by Clauset, Arbesman, and Larremore found that PhD graduates in business go on to a faculty position at an institution an average of 25-30 positions lower in prestige (e.g., from Harvard to UT Austin). Others, of course, choose to forego an academic career and instead enter into industry, generally in a relatively high paying position in finance, consulting, or tech. Some choose to complete their PhD and then take this path, whereas others elect not to finish the PhD and skip straight to their next career.

Why pursue a business school PhD?

This leads us back to the central question: why complete a business school PhD at all? If you are pursuing a PhD in a business school, it means that you either A) want to devote your time to conducting research and become a business school professor (and think the pros of this career outweigh the cons) or B) think that the PhD will unlock something else important in your life.

For Stephen, “A” was certainly true. He realized that the things he did for fun – write, explore data, and try to understand how organizations and business work – exactly matched the job description of a professor. For you, it is important to make that decision before you begin on the PhD application process and the long path to academia. The PhD can be extremely challenging, and the single best reason to enter into this journey is because you believe that you will be most happy spending your time conducting research.

A previous iteration of Harvard Business School’s website lists three qualities, which Abhishek thinks accurately describe traits needed in potential researchers.

- Curiosity and Vision

- Self Motivation

- Academic Excellence

Good researchers above all seem to have a nose for finding important areas where they can apply the toolbox that they possess. Keen observers of the world and those who are often puzzled by why certain things work the way they do often find careers in research to be immensely satisfying. Academics are closer to entrepreneurs in many ways than would appear at first glance. Academics manage their careers in much the same as entrepreneurs would manage their companies, and the ‘products’ that academics manufacture (their ideas) need to be sufficiently tested, marketed and diffused. While junior professors might often be employed in a department with a large number of people senior to them in experience and rank, such seniority does not imply any compulsion to follow orders as far as research is concerned. Indeed even PhD students are often expected to be independent and self motivated to pursue their own research projects with advisors playing a supporting role. Those who need external control will quickly find themselves lost in graduate programs. Lastly, academic excellence is often taken as a given within the profession. Everyone is expected to have the smarts that it takes to do well in courses (and most schools have an exceedingly bright set of students). Making the transition from being an excellent ‘consumer’ of knowledge to a ‘producer’ takes considerable skill and training in addition to academic smarts. In addition to these three points, Abhishek finds that good researchers frequently possess a talent for clear and precise written communication, a skill that arguably develops as one goes along.