This is an old revision of the document!

Timeline

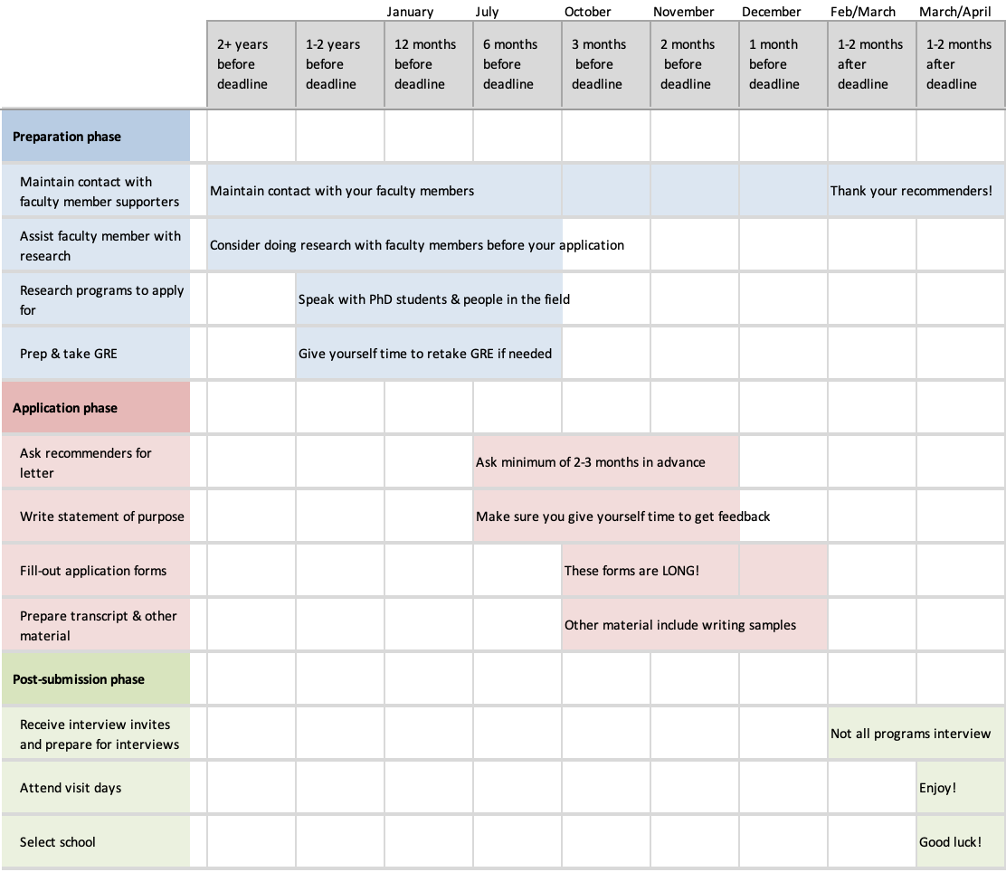

To succeed in the PhD application process, you should give yourself ample time to prepare. As we will detail in the following section, there are numerous parts of the application. Some parts can be done relatively quickly – such as finding and uploading a transcript – and other parts require serious time commitment – such as doing research with faculty members.

In the below section, we outline an ideal timeline for an applicant. Of course, we recognize that most people will not follow this timeline exactly, and many will be able to complete some steps in this timeline more quickly. Rather, this timeline should serve as a benchmark as you go along your PhD application journey. For reference, most programs have application deadlines that range from early December to early January.

Some quick notes on the timeline. We include a section that involves “Assist faculty member with research.” Though this is not 100% necessary, our experience indicates that research experience gives your application a strong edge in the selection process. The reason for this is three-fold: 1) prior research experience shows that you know what you are getting into and demonstrates your commitment to academia, 2) research experience signals some degree of preparation which may make you more successful in the PhD program, and 3) if you work on research specifically in a business school this can give you an “in” to the research community you are hoping to join. Notably in our survey, we found that 44 of our 46 surveyed admitted students had some form of research experience before applying. We will discuss this step in more detail in the section on the “the RA path to the PhD.”

We do not include your graduate or undergraduate studies as part of the timeline, though they remain important in the application. Broadly, the expectation is that you perform well during both of those periods. Of the admitted students we surveyed, the average GPA was roughly a 3.85 with a standard deviation of .12. However, we saw GPAs in the survey range from 3.5 to 4.0. In general, the common wisdom is that a strong GPA is necessary but not sufficient for a successful application.

We recommend that applicants get ahead of the schedule for applying. One faculty member at HBS, who completed their PhD at Stanford in 3 years, advised that you should be done with almost all parts of the application by August or September (which is even more aggressive than our timeline above). Front-loading your application efforts provides more ample time for revision and can reduce the stress during the final few weeks of submission.

Choosing Where to Apply

One of the most important steps before beginning the application is to identify the PhD programs to which you want to apply. In general, applicants should first select their broader field of interest (e.g., accounting, finance, business economics, strategy, etc.). Next, they should begin to identify some questions or topics they find interesting (e.g., social networks, status hierarchy, VC flow of capital, etc.). Finally, after selecting their intended field and topics of study, they should identify the top programs (and specific faculty within those programs) that match their own particular research interests.

Choosing your field and topics of interest

Business academia is split into numerous fields and subfields within which you must identify your particular interests. In general, business school research draws from a set of disciplines such as economics, sociology, psychology, and to a slightly lesser extent other fields such as history, statistics, and political science. Over time, business school researchers have developed their own fields such as organizational behavior, accounting, finance, and strategy. The best way to gain an understanding of these fields is to look at the types of academic articles that these researchers are publishing. It is important to have a general sense of the field of your interest and the types of questions that it does (and does not) cover.

From there, it is important to ask yourself questions about the topics that interest you. Megan, for example, knew she was interested in emotions and prosocial behavior because she had enjoyed assisting with research in those areas, and this led her to consider programs in management and organizational behavior (micro). Stephen, on the other hand, was interested in physical space, social networks, and worker mobility. This led him to look at programs that covered these topics, which were management or organizational behavior (macro). If you are having difficulty honing your own interest, a good way to explore is by reading the major journals in the field (e.g., Academy of Management Journal for management, Strategic Management Journal for strategy, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology or Journal of Applied Psychology for social psychology and micro organizational behavior). While preparing your application you should have a general idea of your research interests and specific topics you can discuss in your application materials; that said, no one will force you to continue doing research on the topics you mentioned in your application. So, this is meant to be directional but not binding.

Choosing the programs to apply to

After identifying your topics of interest comes the difficult task of choosing which programs to apply to. In general, there is a limited amount that you can learn online about a program, and because the characteristics of a program can change dramatically as different faculty members join and leave it is important to seek out up to date sources of information. We suggest four main ways to learn about your specific programs of interest.

Method 1) Online search for programs & faculty members

Even with its limitations, an online search is often the best way to get an initial feel for a program and to identify which programs are out there. When reading through program websites, there are three important factors to note: the faculty and their research interests, the careers (academic or otherwise) that their students go on to lead, and the location of the school. When casting your net for potential programs, keep in mind that MBA program prestige rankings do not correlate perfectly with the quality of business school PhD programs. There are many schools outside of the Ivy League or top MBA rankings that have excellent business school faculty and publish research in leading journals.

The most important characteristic of a program is its affiliated faculty members. After identifying which faculty members are affiliated with the program, it is then useful to look at the type of research that they are publishing by using Google Scholar or looking at their most recent CV. Even a cursory look at the abstracts of the recent papers written by an academic can give you a sense of some of their research interests. (Though not all! Remember that the publication timeline is long, so a faculty member’s recent publications may no longer reflect their current research interests.) One way to find the most recent work of a faculty member is to look at conference websites – this is the research for which faculty members are seeking feedback from peers, so it is generally newer work. Students should focus on applying to programs with multiple faculty members (2-4) whose research interests overlap with their own, ideally ranging in level from assistant to full professor.

After graduation, what are your possible prospects? For most business fields, the top 10-20 schools all recruit from one another. So, by going to one of these schools, you enter into an elite pool of candidates for an academic job. With that said, some schools consistently perform better than others when it comes to job placements. When conducting your due diligence on programs, look at the past ten years of academic and non-academic placements (which is often at least partially available on the program website). This will give you an idea for the type of school (or company) where you should expect to work post-graduation.

Take note of where potential programs of interest are located. In multiple conversations Stephen had, senior faculty emphasized the importance of location when choosing a school. Though the school itself is important, you are also making a decision about where you will live for the next five to six years. That is a significant part of your life! When choosing a school, it is also important to choose a place where you would actually want to live.

Method 2) Speaking with friends and mentors in the field

Reaching out to your connections in the academic world is a useful way to gain information about the different programs. In general, we recommend reaching out to a broad set of people even if they are not directly in your field of interest. For example, Megan reached out to her friends from her undergraduate psychology program who had gone on to PhD programs or faculty positions in psychology. Early on, these contacts can provide directional advice about programs and can help you connect with others in the field.

Method 3) Reaching out to current graduate students [Pro tip]

One of the most useful cohorts to reach out to is current graduate students. In particular, look for graduate students with similar interests in the same fields that you are targeting. Because graduate students recently went through the application process, they can provide tactical guidance on their own programs and how to approach the application. In particular, ask graduate students about their experience in their program and the faculty members they know in the department. One tip while talking with students is to pay attention to what they do not say about the program or advisors. In general, people speak very positively about their own programs and want to convince you to join. However, if they do not like someone or want to avoid talking about an issue with the program, they may not mention it. For example, at one program (left unnamed for anonymity), Stephen asked a current student about which faculty members he should consider as possible advisors. The student listed 4-5 names, but notably omitted a faculty member who had clear research alignment with Stephen. What Stephen realized through follow up conversations was that this advisor had a notorious reputation for advising students. The student had answered Stephen’s question, but the omission was more telling than the answer itself.

Method 4) Reaching out to faculty members

Finally, reaching out to faculty members of interest can be a useful way to gain information about programs and to introduce yourself to potential advisors. Because faculty members are busy, we would suggest reaching out to those faculty members with whom you share A) a clear research alignment, B) a connected trait (e.g., same undergrad school, same hometown, etc.), or C) a mutual connection. In general, faculty members are often open to talking with serious applicants and discussing their own research. Whenever possible, in-person meetings are more effective and produce a more positive memory than meetings online. While reaching out to faculty members can be helpful in the application process, it is not strictly necessary. For example, Megan did not contact faculty members at her target programs prior to applying.

Ways to distinguish programs

There are numerous ways to distinguish programs. We identify a few axes to consider when deciding where to apply. Oftentimes it will be difficult, if not impossible, to understand these differences between programs without speaking to people in them or in the field.

Disciplinary vs. phenomenon-driven

One core difference between programs is how “disciplinary” or “phenomenon-driven” they are. In this case, disciplinary refers to the original discipline that the field emerged from. Organizational behavior (micro), for example, emerged from social psychology and the two disciplines overlap considerably in terms of research topics and methods. When we call a program more disciplinary, we mean that it has a deeper focus on that discipline (e.g., psychology) and its faculty likely publish more often in discipline oriented journals.

Programs which are less disciplinary are generally more phenomenon-driven. This means that their research is focused on understanding specific events, processes, and trends that are currently relevant in business contexts. For example, studying the impact of mentorship on promotion outcomes would be a more phenomenon-driven approach, whereas examining how power influences approach behaviors would be considered more disciplinary (in this case, psychological). In most fields, more disciplinary programs are considered slightly more prestigious. In practical terms, this means that you can graduate from a more disciplinary program and place in a faculty position at a less disciplinary program, but it is more rare to go the other way.

Degree of specialization in level of analysis

A related but distinct axis on which to compare the training focus of programs is the degree to which they expect students to stay within a particular level of analysis or set of methods. For example, some organizational behavior programs maintain strong divides between the micro (psychological) and macro (sociological) faculty members and students, whereas other programs train students thoroughly in both methods and embrace “meso” approaches and methodologies. Similarly, some strategy programs have a clear boundary between economic and sociological orientations, whereas others embrace mixing the two.

Apprenticeship model vs. entrepreneurial model

Another key difference between programs is the extent to which they are “entrepreneurial” in nature. When a program is entrepreneurial, this means that there are very minimal support structures in place for the student. This provides flexibility for the student to pursue their interests, but it also requires students to identify and connect with faculty members on their own initiative to successfully conduct research.

Apprenticeship models involve a much more structured path for a student. When a student enters a program, they are assigned a faculty advisor. They then work with this faculty advisor on their research agenda, starting as a research assistant and then working to be a co-author. Oftentimes apprenticeship models are paired with “labs” in which people work under 1-2 faculty members interested in similar topics. One advantage of an apprenticeship model is the speed and ease with which graduate students earn publications. However, on the job market, candidates are often penalized for being too similar to their faculty advisors and failing to establish their own research identity.

In general, the top business school doctoral programs all follow some version of the entrepreneurial model, with only minor differences in the degree of support provided.

Senior-faculty heavy vs. junior-faculty heavy

There is significant variation across departments in the percentage of senior and junior faculty. Some departments are very senior-heavy, meaning that they have many tenured faculty but fewer junior faculty (e.g., assistant professors). Other departments have a handful of senior faculty, but are dominated by a younger set of professors. Of course, some departments sit in the middle, but it is often possible to characterize departments as senior- or junior-dominated.

The advantage to collaborating with more senior faculty is that they can provide high-level, strategic advice on your career. Additionally, their clout and social connections can serve you enormously when you go on the academic job market. The drawback is that senior faculty are often less research active, meaning you will collaborate with them less and projects may proceed more slowly. Junior faculty-heavy programs, on the other hand, provide you with ample productive collaborators for your research. As research is the primary criterion for junior faculty to gain tenure, their incentives are aligned with yours to produce a large volume of high quality research. However, they may have less clout in the field, which could make your job search more difficult.

An ideal program will have a mix of both senior and junior faculty with whom you can collaborate on research so that you can balance the pros and cons of each.

To how many programs should I apply?

In general, we recommend applying to more programs rather than fewer, given the low admission rates at each of these programs (roughly 4-7%) and the low marginal cost of applying to an additional program. In our case, Stephen applied to 7 programs and Megan applied to 11 programs. Our survey respondents applied to an average of 8 programs (with a standard deviation of 5.5). That said, we do not think you should apply to any programs that you would not consider attending – this is a waste of effort on your part and potentially could block out another deserving candidate.

Application Materials

Your application materials will be the main (if not only) input that admissions committees use to evaluate you, so it is important to invest the time and effort to get them right. Your main goals in preparing your materials should be to A) highlight your strengths as a candidate and B) meticulously meet every requirement for the school you apply. Taken together, your application materials should demonstrate your intelligence, persistence, intellectual creativity, and clear understanding of the realities of the path ahead.

GRE/GMAT

At the time this guide was written, all major business school PhD programs require that applicants submit either GRE or GMAT scores, including verbal, quantitative, and analytical writing scores. Most do not state a preference between the two tests, so you can choose whichever one you think will give you a higher score. From our survey of admitted students, 96% submitted GRE scores for their applications, and this seems to be the current standard across all programs. Both Stephen and Megan took the GRE, so the following information will be most relevant to that test.

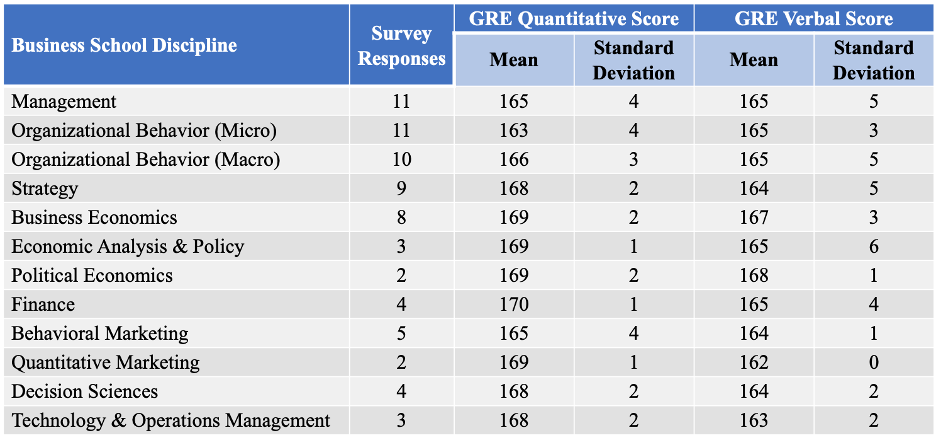

Business school PhD programs seem to pride themselves on maintaining high GRE/GMAT averages for admitted students. Many programs include these metrics on their admissions websites (often in FAQs), so you can check the figures for your target schools to see how you match up. For example, in 2019 Wharton listed their average GRE verbal score as 163 (90th percentile) and their average quantitative score as 167 (91st percentile). It is important to note that these averages usually include all admitted students across the business school PhD program, including those in finance, accounting, management, and marketing, so the average score may not be very informative for your particular area of interest. For example, one would expect that successful finance PhD applicants might have a higher average quantitative score than organizational behavior applicants, and within organizational behavior macro applicants may have higher quant scores than organizational behavior micro applicants. If your intended research methods require more intense quantitative skills, you can reasonably expect that the average quantitative score will be higher.

The table linked above shows the number of responses, mean, and standard deviation of GRE scores by business school discipline from our survey of admitted students. Of the 42 individuals who reported both GRE scores and disciplines, 22 applied to multiple disciplines; their scores are included in the results for each discipline to which they applied. Please note that the survey respondents were admitted to R1 PhD programs, which represent only a small portion of all programs. Therefore, these scores are higher than may be necessary to gain admission to other high quality PhD programs.

The table linked above shows the number of responses, mean, and standard deviation of GRE scores by business school discipline from our survey of admitted students. Of the 42 individuals who reported both GRE scores and disciplines, 22 applied to multiple disciplines; their scores are included in the results for each discipline to which they applied. Please note that the survey respondents were admitted to R1 PhD programs, which represent only a small portion of all programs. Therefore, these scores are higher than may be necessary to gain admission to other high quality PhD programs.

Once you have a handle on what score you need for your target schools, it is time to understand the gap between your current and desired test performance. For some, the GRE is the easiest component of their application to prepare. For others (such as Megan), it was the most difficult. It is a good idea to take an official ETS practice test at least six months prior to your intended test date so you can develop a systematic and sustainable plan to address your weak points. If you find you have a large gap to close, Megan recommends dedicating about ten hours per week (ideally spread across five to seven days of the week) to practicing with official ETS material ( Greg Mat’s YouTube videos are an excellent free resource), punctuated by practice tests weekly or biweekly (there are multiple free ETS practice tests available online). It can be helpful to supplement your preparation with test prep programs such as Magoosh, but bear in mind that only genuine ETS questions can rigorously prepare you for what you will encounter on the GRE. If preparing for the GRE is causing you a great deal of anxiety, it may be worth enrolling in a class or hiring a tutor to provide you with structure and outside validation of your effort and progress. Plan to take the test two to three times to reach your desired score, and arrange for your final test date to occur at least three weeks prior to your first application deadline.

If you have done everything you can and your score is not what you hoped, do not let that hold you back from applying. Megan almost did not apply in 2019 because her GRE quant score (160; 73rd percentile) was lower than all posted averages, but decided to give it a shot anyway with positive results. Based on conversations with faculty members and other admits, it appears that the GRE/GMAT score is used mainly as a general cut-off in the review process; however, a high GRE score is only a baseline requisite and is not nearly sufficient to secure admission.

CV

Your CV (curriculum vita) should include all the most important information that you would like faculty to consider as they are reviewing your application. CVs are similar to resumes in the sense that they should summarize your qualifications, skills, and experiences, but they are allowed to be longer than the standard one page so that they can provide a full record of your contributions to academia. Your CV is a good place to include the technical details of your research projects (i.e., particular tools or methods you used or skills you built), especially if you find that your statement of purpose is being bogged down by these details.

CVs usually follow a consistent format, which you can see by looking up any academic’s CV or by searching online for a CV template. While it is advisable to match your CV’s aesthetics to the norm, you should feel free to pick and choose which content sections to include. Stephen, for example, decided to include the abstracts of all the research articles he had worked on (e.g., his senior thesis) so that he did not have to include it in the statement of purpose. Similarly, you may want to make up your own novel section to highlight your technical skills. On the other hand, you may not have any grants (most applicants won’t), so you can forego that section entirely.

Generally, CVs can be as long as necessary to cover all of your accomplishments, but some programs impose a two page limit. It may be a good idea to stick to that two page limit (as Megan did) so that you can 1) use the same CV for all of your applications and 2) acknowledge the value of brevity in this situation where very busy faculty seek to quickly understand who you are as an applicant.

You can see example CVs submitted by successful applicants in this folder.

Academic Record/Transcripts

You will need to submit transcripts for all post-secondary institutions you have attended (anything after high school, i.e., undergraduate or graduate education and study abroad programs) either as a PDF or as a mailed copy. For both of these options, you will need to request your official transcript from your school, usually through an online portal. It is a good idea to carefully read the instructions for submitting transcripts for each school to which you intend to apply a month or more before the deadline so that you can mail transcripts as needed.

Writing Sample

Some programs will ask you to submit a sample of your academic writing. The ideal item to include here would be a paper or thesis (master’s or undergraduate honors) that you have already written and reviewed with multiple academics. Megan used her undergraduate honor’s thesis (completely untouched since its completion three years before applying) as her writing sample for applications. Stephen submitted a paper that he had published with a mentor that was loosely based on his senior thesis. If you really do not have a good writing sample already prepared, spend the summer before applications writing and polishing one appropriate to the discipline. The writing sample seems to function as another (somewhat peripheral) measure of your research experience and thus your credibility in saying you intend to pursue an academic career. The importance of the writing sample seems to vary by applicant; for some, it was a topic of conversation in many interviews whereas for others it was never discussed.

Letters of Recommendation

Most programs will require you to include three letters of recommendation with your application (with some asking for only two and others allowing up to five). Both the source and content of your letters are very important, and together they should send the message that you demonstrate excellent potential for a career in research at a business school.

The business school academic community is small and tight-knit, and your network can play a key role in your success in the application process. Ideally, your letters should come from business school faculty members with whom you have worked on research (and the more senior and well-known the faculty member, and the closer their connections to your programs of interest, the better). They will be in the best position to speak to your potential, and their letter will get you noticed by the other faculty members in their network. If you cannot get a letter from a business school faculty member, the next-best option is to request one from a faculty member in another discipline. If you find that you can't identify enough letter writers in your immediate academic environment, consider taking a non-degree course at a local university, engaging with the professor, and asking them to write a letter. Once you have exhausted your options within academia, you can then consider soliciting letters from your other connections (such as work supervisors).

The content of your letters is equally (if not more) important. A vague letter with faint praise from a famous professor will not help your case for admission, whereas a specific and detailed letter with glowing remarks from a relative unknown in another discipline may take you far. To set yourself up for a high quality letter, you should find opportunities to increase the breadth and depth of your research experience with faculty members. You can do this by contributing to multiple research projects, taking on a leadership role, and having conversations with faculty members about your research ideas and interests. If you have someone who you think is a potential letter writer, make sure to keep in contact with them even after graduation. This can include email updates, dropping by their office when you are in town, or discussing your PhD plans with them when you begin the application process.

It is important to be organized and purposeful about obtaining your letters of recommendation. If you have been out of contact with a potential recommender for some time, reach out to them as soon as you decide to apply to re-introduce yourself, discuss your plans, and ask for their support. Rather than asking if they are willing to write you a letter, instead ask if they feel they would be able to write you a strong letter. If they express any misgivings, you should thank them for their honesty and move along to another option. If they confirm that they are able to recommend you highly, you can then have a discussion about what experiences or characteristics they might highlight in their letter. This may feel like overstepping - after all, they are free to write whatever they like and you are not entitled to read it - but it can be quite helpful to remind them of the details of your work together (especially if significant time has passed) and to give them a sense of the story you intend to tell with the rest of your application materials.

Once you have your letter writers lined up, you must turn your attention to logistics management. Much helpful advice for tackling this challenge has already been shared (notably, Susan Athey’s list of tips). Your goal should be to make it as easy as possible for them to submit their letters on time and to the correct schools. This will likely entail A) emailing them a summary of your shared research or other experiences with the faculty member (make it easy for them to remember!), your draft statement of purpose and CV, and a list of all the schools to which you are applying and when you intend to submit your application, B) coordinating with the professor (and potentially their faculty assistant) on when to trigger the email invitations for them to submit each letter (some recommenders will prefer that you invite them to submit letters for all applications at once so that the links are easy to find in their inbox), and C) following up with them regularly (and politely) until they submit their letter to each school. Once they have finished submitting their letters, it is a great idea to mail them a handwritten thank you card to communicate how much you appreciate their support.

Statement of Purpose

The statement of purpose (SOP) is your opportunity to communicate a compelling narrative about who you are, where you come from, where you want to go in the future, and why [insert school here] is the best academic community for you to join as you ascend to greatness. The SOP is a key part of your application and deserves a significant investment of your time and effort.

Before you can communicate your research identity to admissions committees, you need to figure it out for yourself. The most important step here is to understand your research interests to the best of your ability. Once you have that piece, you will be able to sort through your experiences to tease out the important moments that led you to those interests so that you can craft a cohesive narrative. The best way to narrow down your interests is to engage with a lot of research. Read many journal articles, and take note of the ones that excite you most. Stephen, for example, read a number of research articles across micro and macro organizational behavior to choose which side he fell on.

Once you have amassed a robust cloud of potential research areas, there are two paths you can take. One option is to find a connecting thread between a handful of the ideas that spark the most passion for you, and build your essay around that core. Another option is to write multiple versions of your essay that highlight different clusters of your interests, and submit these more diverse essays to each of your target schools accordingly. Rest assured that no one expects your research interests to be fully formed at this point, and they will not force you to study the specific topics included in your essay. However, you may find more success if you write as if you know exactly what you want to study and why, even if internally you feel less certain. The objective is to demonstrate that you understand the field well enough to articulate interesting and testable research questions.

There are many different ways to write a great statement of purpose. Successful versions can vary on many factors, including their focus on personal anecdotes and underlying motivations vs. impersonal discussion of research experience and interests, past accomplishments vs. future ambitions, and how exactly the connection is made to your target program. For examples of these different options in practice, read through this folder with sample statements of purpose contributed by successful applicants in the 2019-2020 application cycle. For additional example essays across a diverse array of academic fields (and helpful exercises to kickstart the writing process), check out the book Graduate Admissions Essays by Donald Asher. For those who wrote essays for college admissions in the US, know that this process is very different. The focus of these statements is much more on what you can do and have already done in research and much less on telling an intricate narrative about your life’s journey. It is advisable to keep the statement of purpose clear and concise; you will have the opportunity to address the breadth of your interests and personal motivations in the interview process.

Regardless of your stylistic and structural choices, one of the most important things you do in your essay will be to clearly demonstrate how your research ambitions and interests make you an excellent candidate for your program of interest. Tactically, this will likely involve emphasizing different aspects of your research interests for each program, as well as mentioning potential faculty collaborators by name. To do this, you will need to gain an understanding of the research being conducted by the faculty at each of your target programs by reading their faculty profiles, CVs, personal websites, and research articles. We recommend keeping this information in a spreadsheet or other document to stay organized. Once you have identified the handful of faculty members whose interests overlap with your own, you can then highlight those interests more prominently and propose potential areas of collaboration in your essay. There is no need to change your interests entirely for each school. Instead, the objective is to find and emphasize points of overlap and connection that fit each school’s academic community.

Once you have written the core content of your statement, is it time to edit ruthlessly. Most schools set a limit of 1000 words, with a few allowing up to 2000. It is important to get multiple people to review your statement. If you feel that you need significant improvement on the less academia-specific aspects of your essay such as the logical flow and sentence structure, be sure to get feedback from people close to you, such as friends and family, before asking your more academic reviewers. Receiving feedback from current professors and graduate students in your field of interest is the best way to ensure that your essay is up to par. They will be able to notice the logical gaps, unfortunate language choices, or annoying cliches that could otherwise turn off admissions reviewers. Be sure to leave significant time (a few weeks to a month) for this review process.